Framing the O’Brien Collection

Tracy Gill, New York

Autumn 2014. It was a memorable November day when the O’Briens strode into our lower Manhattan frame gallery. They took us by surprise with a significant search request, to find a good period frame for their William H. Bartlett painting, The Last Brief Voyage: A Connemara Funeral. This dramatic and poignant scene measures over four feet high and seven feet across—it was understood that sourcing an oversized antique frame of the right origin, style, and date could be difficult.

Yet, with thousands of frames in our inventory, collected over decades, we happened to have just the right frame in our lower gallery, acquired years before on one of our European frame-buying trips. We pulled from the racks a grand eighteenth-century English Carlo Maratta-style frame, made of hand-carved wood and still retaining its original gilded surface after two hundred years (fig. 1).

fig. 1

William Henry Bartlett

The Last Brief Voyage: A Connemara Funeral | 1887

53.5 in. x 83.5 in., Oil on canvas

18th-century English frame, Carlo Maratta style, gilded hand-carved wood with ebonized scotia.

Though the Bartlett painting had been separated from its original frame some time ago, when it was first exhibited in 1887 at the Royal Academy in London, a “Carlo” would likely have been the artist’s traditional frame of choice. Further, we knew that this style frame often had muted gilding with a black-painted scotia or central hollow, and in this case, the black border was fitting for the solemn narrative of the memorial scene.

As framers, we have had fun with creative surrounds for many works of art. However, as scholars and consultants, it is our job to advise when a period-correct frame is needed. This is academic framing, the kind we most often do for museums, where purist, historical, frame and painting pairings are required.

However, while a frame in a museum setting needs to be both historically and aesthetically appropriate, the private collector has more leeway in forming an overall presentation of their collection according to their personal aesthetic. In this case, the O’Briens clearly understood that the proper period frame would make a big difference in the presentation of Bartlett’s historical narrative. The academic approach was successful.

Our relationship with The O’Brien Collection had begun a few months earlier. We were contacted by the late Christopher Monkhouse, Eloise W. Martin Chair and Curator, European Decorative Arts at the Art Institute of Chicago, who sought us out to locate a “Rococo Revival gilt frame from the 1840s for James Christopher Timbrell’s Carolan, the Irish Bard exhibited at the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition in London in 1844.” We researched and proposed three antique English frames for this marvelous painting and sent photomontage images to illustrate how the painting would appear in each. Rather than a curvy rococo style, the O’Briens chose a more historically appropriate straight-edged model, a scarce c. 1830s–40s English Academy frame that we sourced from an English collection. As with much of our own period frame inventory, the owner had been holding on to the empty frame, waiting for the right painting to need a mate. This was it (fig. 2). The frame was shipped from London, restored in our New York studios, and arrived in Chicago to take center stage on the museum wall for the 2015 exhibit Ireland: Crossroads of Art and Design, 1690–1840.

fig. 2

James Christopher Timbrell

Carolan, the Irish Bard | 1844

40.25 in. x 57 in., oil on canvas

c. 1830s-40s English Academy frame, gilded cast ornament on wood.

Since then, it has been our pleasure and honor to consult and provide frames for over seventy-five works of art in The O’Brien Collection. This is the greatest number of fine art frames we had provided to any one client, apart from the Art Institute of Chicago, for whom we have been frame consultants since 1997. There are numerous reasons why so many paintings in one collection were reframed. Choosing frames for artwork can be a complex process. We often propose remotely, particularly for museums and far-flung collections when shipping the valuable art to our New York frame gallery would not be feasible. But it is always best when we can view the art in person. So we traveled to Chicago to see The O’Brien Collection in situ, to understand how their art was incorporated into home life. We also examined works in storage and advised on what frames should be kept and which might best be changed for future display.

We were able to assess and compare works by the same artist and see varied selections of paintings displayed together. We flagged many that would benefit from a frame change. Some had inexpensive ready-made frames placed on the art years before coming into the Collection, perhaps chosen by an auction house or painting dealer who did not want to go to the expense of a good frame. For others, the frame was chosen before the artist became recognized and collected by a wider audience, and the art now warranted a more thoughtful frame pairing. We recommended replacing frames that were minor examples or proportionally incorrect—too thin or too heavy—and profiles that did not complement the art. Some styles were overly decorative, distracting from the artist’s intent, or brightly gilded where a more subdued or pared-down frame model would better suit.

For some collectors, a picture frame might be considered secondary to the painting, serving only the necessary purpose to contain and protect the canvas, or perhaps as a “decorator-approved” choice matched to the decor and unrelated to the art.

The proper frame can enhance a painting, but the wrong choice can work against it by drawing attention away from it or underplaying the importance of the art. A frame can give a clue to the value of an object, but our main concern is proposing a frame that enhances the strength of the artist’s vision by complementing the composition, colors, and medium. Unless it’s an academic decision, it comes down to an aesthetic choice and personal taste.

As the savvy collector acquires more artworks, rearranges their walls, and rearranges again, they will undoubtedly come to ponder how their collection appears in total, at which point the larger art of display enters the picture.

A frame is the edge of the art, a bridge between the canvas and the world surrounding it. In a private collection, this is particularly notable, as the frame also serves as a connection with interior decor and the lives of family and friends interacting daily with the art in their home.

It is always a pleasure for us to advise a serious collector, especially when consulting in depth with a collection over a number of years. This allows us to become closely familiar with the art and the collection as a whole, while still considering the individual needs of each painting.

As each painting is considered individually, the art of the frame in relation to the art on the canvas becomes more apparent and serious consideration of the artwork’s historical context—including the date it was made, the intent of the artist (some artists chose or designed and handcrafted frames for specific canvases), and cohesiveness of the collection—becomes tantamount. Over time, the serious collector becomes a connoisseur, collecting with knowledge on two levels: the art and the frame.

Although the first O’Brien paintings we framed dated to the 1800s, we soon learned that much of their painting collection dates to the twentieth century. This shifted our framing focus in an exciting direction. Most nineteenth-century frames were created by workshops using mass production techniques, such as applying gilded cast ornaments on wood moldings, to manufacture frames in whatever style was in vogue that decade. Early twentieth-century frames evolved to reflect changes in the world of art. Twentieth-century modernity called for new varieties of frames crafted by artists and custom-made to benefit the paintings within. Frames tailored in form and tonality to harmonize with specific works of art began to replace prevalent Victorian manufactured frames, which had often meant that an entire collection might have had the same frame design regardless of difference in artists or subjects. By the early twentieth century, handcraftsmanship in frame making marked a new creativity in frame designs and a return to the artisanal skills of earlier centuries, before the Industrial Revolution.

Over the years we framed a few more O’Brien paintings in a traditional academic style. The gilded neoclassical frame on Nathaniel Hill’s Breton Peasants at a Convent Door (c. 1881) is an international style, popular in the mid-to-late nineteenth century (fig. 3). The egg and dart and fluting, derived from the vertical fluted design of Ionic columns, creates a formal surround for this genre scene. A pair of early nineteenth-century English Hogarth frames, ebonized wood with gadrooned top edge and gilded running pearl ornament near the sight edge, were just right for two Charles Cook paintings, Pat Contemplating Amerikey.

fig. 3

Nathaniel Hill

Breton Peasants at a Convent Door | 1881

14.75 in. x 20.25 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1860s American frame; Doll & Richards, Boston makers; gilded applied composition ornament on wood.

As our framing collaboration proceeded, we became less concerned with the academic approach. We were impressed by and appreciated the O’Briens’ overall process, wherein their collection was a living, changing entity. They are the only collectors we have worked with who might choose more than one frame for a single painting depending on where the canvas would hang—whether in a familial setting over the fireplace or perhaps changed to a more formal “dress” to be loaned out for an exhibition.

We learned their frame preferences and sought out period frames that would fit their personal aesthetic and overview of the Collection, while still adhering to our professional recommendations for affinity in period and style. Aside from the few academic pairings mentioned, for much of the Collection, we were less concerned about matching dates and more thoughtful about complementing the look of the art and its subject or context—whether a barroom scene or a local landscape. The O’Brien paintings individually benefited from the large selection of early to mid-twentieth-century frames that we had been collecting for many years; this was a rare convergence, as it is unlikely a large Modernist frame inventory with such diverse examples of the period will be available again.

Several times during the pandemic, our shipper drove a truck full of frames from New York to Chicago. Over a hundred frames made that trip, allowing the O’Brien team to move our frames around the house and hold them up to numerous canvases over several days; it was an opportunity to try many frames on many paintings, like fitting suits at a bespoke couturier. When the frames returned to New York, we would customize the chosen ones for specific paintings, resizing to fit, and restoring or adjusting colors and patinas as needed. Our studio artisans are accustomed to exacting work on frames for museums and having the time to focus on one collection was valuable.

Whereas early twentieth-century art in Ireland had been largely framed in very basic styles to push forward sales by auction houses and the predominant Dublin dealer Victor Waddington, few of these commercial frames were of good enough quality to signify the increasing importance or value of the paintings nor to display in a future collection of the O’Brien’s caliber. The existing frame models, with redundant manufactured designs—wide white and gold moldings, flat white and silver, black with a gold fillet, or protuberant interpretations of French motifs—simply do not stand up to the test of time for these significant works.

The O’Briens studiously handpicked frames for each painting, from elegant gilded models by illustrious makers, such as those on Paul Henry’s Windy Day, Kerry and John Lavery’s The Lakes of Killarney, to sophisticated white frames with rubbed polychrome or gilded accents, like the superb examples chosen for John Luke’s The Bathers, Charles Lamb’s The Egg Seller, and Walter Osborne’s Milking Time in St. Marnock’s Byre. William Leech’s Beach Parasols, Concarneau, was reframed in a gilded molding whose rippled motifs enhance the active brushwork of a wind-blown scene; American artist Childe Hassam specified this elegant design for a 1918 exhibition of his series of flag paintings at Durand-Ruel Galleries, New York. The O’Briens also selected the dark wood frame for Erskine Nicol’s A Shebeen at Donnybrook and many interesting carved and polychromed variations of wormy chestnut for paintings by William Conor and others. Every frame chosen for the Collection was carefully considered (figs. 4–10).

fig. 4

Paul Henry

Windy Day, Kerry | 1934-35

16 in. x 24 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1910-1920 American Arts and Crafts frame, Milch Galleries, New York makers, pale 20-karat gilded hand-carved wood with stippled gesso panel.

fig. 5

John Lavery

The Lakes of Killarney | 1913

24 in. x 29.25 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1907 American Arts and Crafts frame, Foster Brothers, Boston makers, gilded hand-carved wood.

fig. 6

John Luke

The Bathers | 1929

20 in. x 24 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1940-50s American Modernist frame, House of Heydenryk, New York makers, polychrome with gilded and incised details on hand-carved wood.

fig. 7

Charles Lamb

The Egg Seller | 1930s

24 in. x 20 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1930s German Modernist frame, Pfefferle, Munich makers, gilded and polychromed hand-carved wood, red wax seal, verso: PFEFFERLE/ MUNCHEN / SE… 18…

fig. 8

Walter Osborne

Milking Time in St. Marnock’s Byre | early to mid 1890s

25 in. x 31 in., Oil on canvas

Mid-20th century American Modernist painting frame, House of Heydenryk, New York makers, gilded and polychromed hand-carved wood.

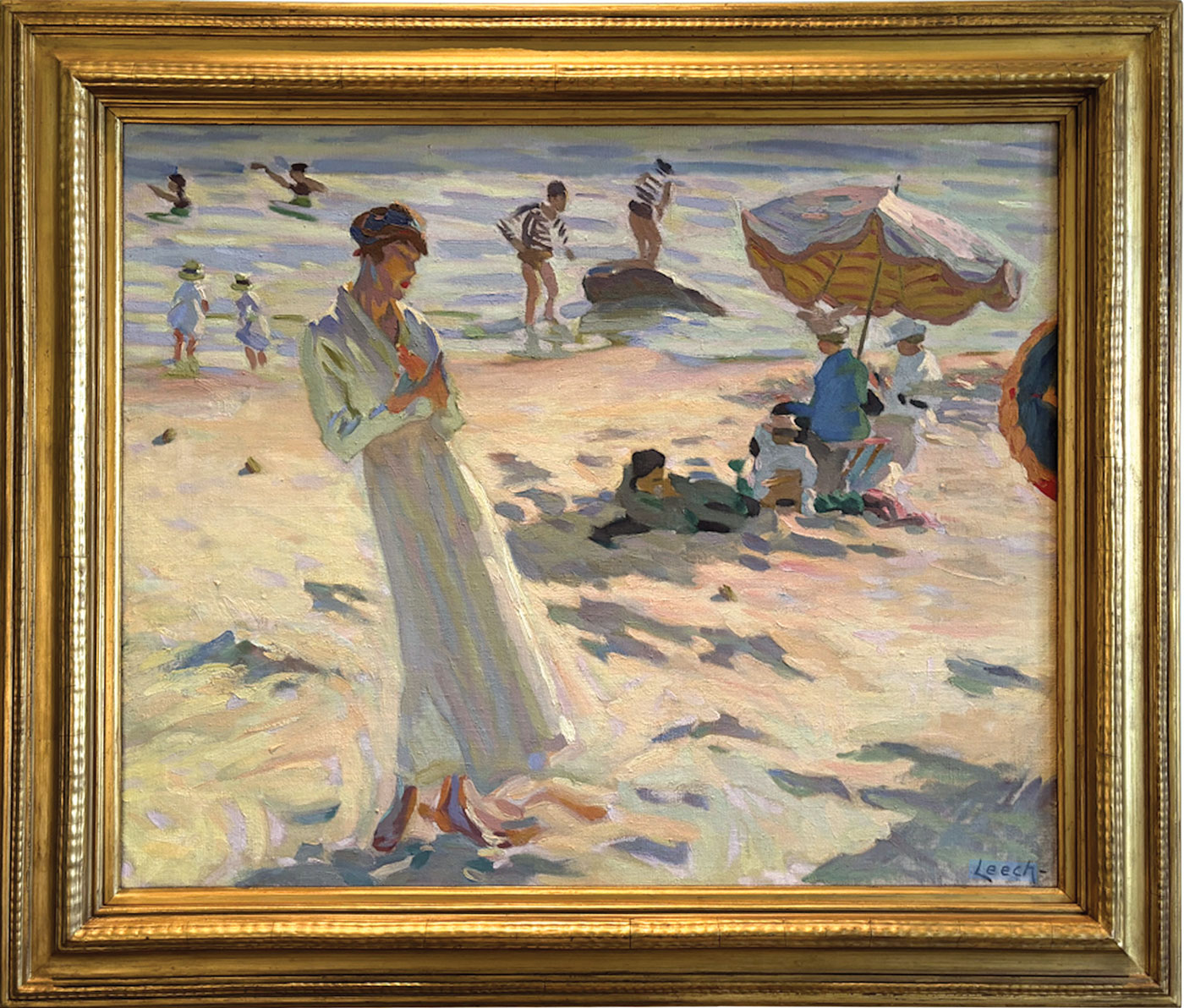

fig. 9

William John Leech

Beach Parasols, Concarneau | 1920

22 in. x 27.25 in., Oil on canvas

Early 20th-century American frame, gilded applied composition ornament on wood.

fig. 10

Erskine Nicol

A Shebeen at Donnybrook | 1851

24 in. x 34.5 in., Oil on canvas

Early 20th-century American Arts and Crafts frame, Foster Brothers, Boston makers, patinated hand-carved wood.

A certain level of rusticity was perfect for many of the quotidian scenes of working people, local celebrations, pictures of home, and places where friends would gather. We sought out frames that would suit the subjects, colors, and textures of each canvas, paying less attention to a frame’s country of origin or date.

Jack B. Yeats’s A Summer Day is complemented by an eighteenth-century Italian hand-carved wood frame with natural clay color panels. This look was adapted hundreds of years later by twentieth-century Modernists (fig. 11). Other frames in the Collection with similar appearance were made in the twentieth century, borrowing motifs and techniques of the past and reinterpreting them with a modern patina. Three modern carved wood frames with similar earthy orange tonality were chosen for Lilian Lucy Davidson’s Potato Harvest, Henry Aaron Kernoff’s The Twelve Pins, Renvyle, and William Conor’s At Benediction (figs. 12–14). Displaying these three frames together allows for a visual connection between traditional and contemporary design, and it’s fascinating to understand how frame designs developed across centuries.

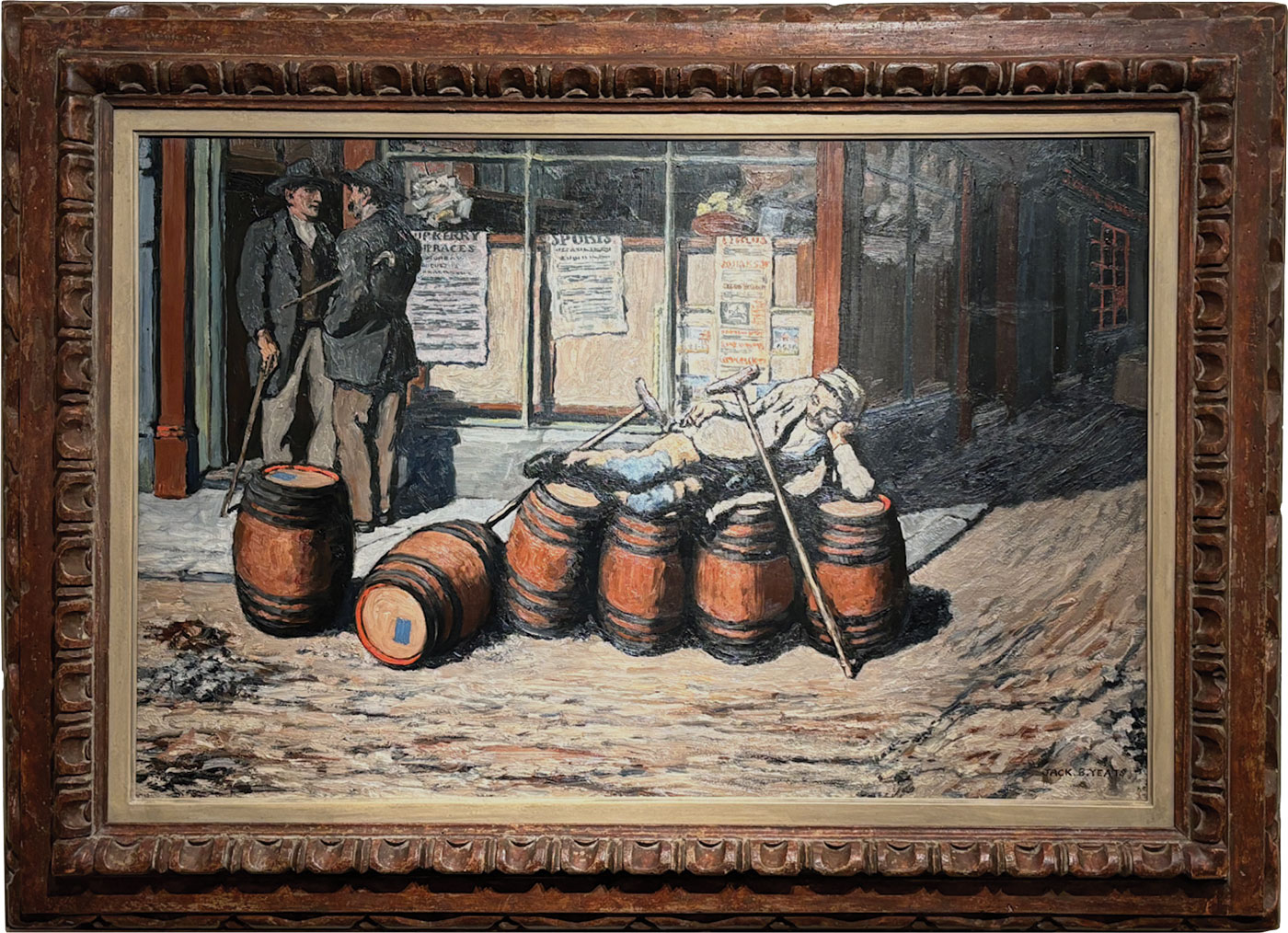

fig. 11

Jack B. Yeats

A Summer Day | 1914

24 in. x 36 in., Oil on canvas

18th-century Italian frame, original gilded and decapé red clay on hand-carved wood, antiqued gesso on wood liner.

fig. 12

Lillian Lucy Davidson

Potato Harvest | 1931

29 in. x 39.5 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1950s American frame, House of Heydenryk, New York makers, polychromed hand-carved wormy chestnut wood.

fig. 13

Henry Aaron Kernoff

The Twelve Bens from Renvyle, Connemara | 1937

12 in. x 16 in., Oil on board

c. 1930s–40s American frame, House of Heydenryk, New York makers, polychromed hand-carved wormy chestnut wood.

fig. 14

William Conor

At Benediction | 1918

24 in. x 20 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1940s American Modernist frame, House of Heydenryk, New York makers, polychromed hand-carved wormy chestnut wood.

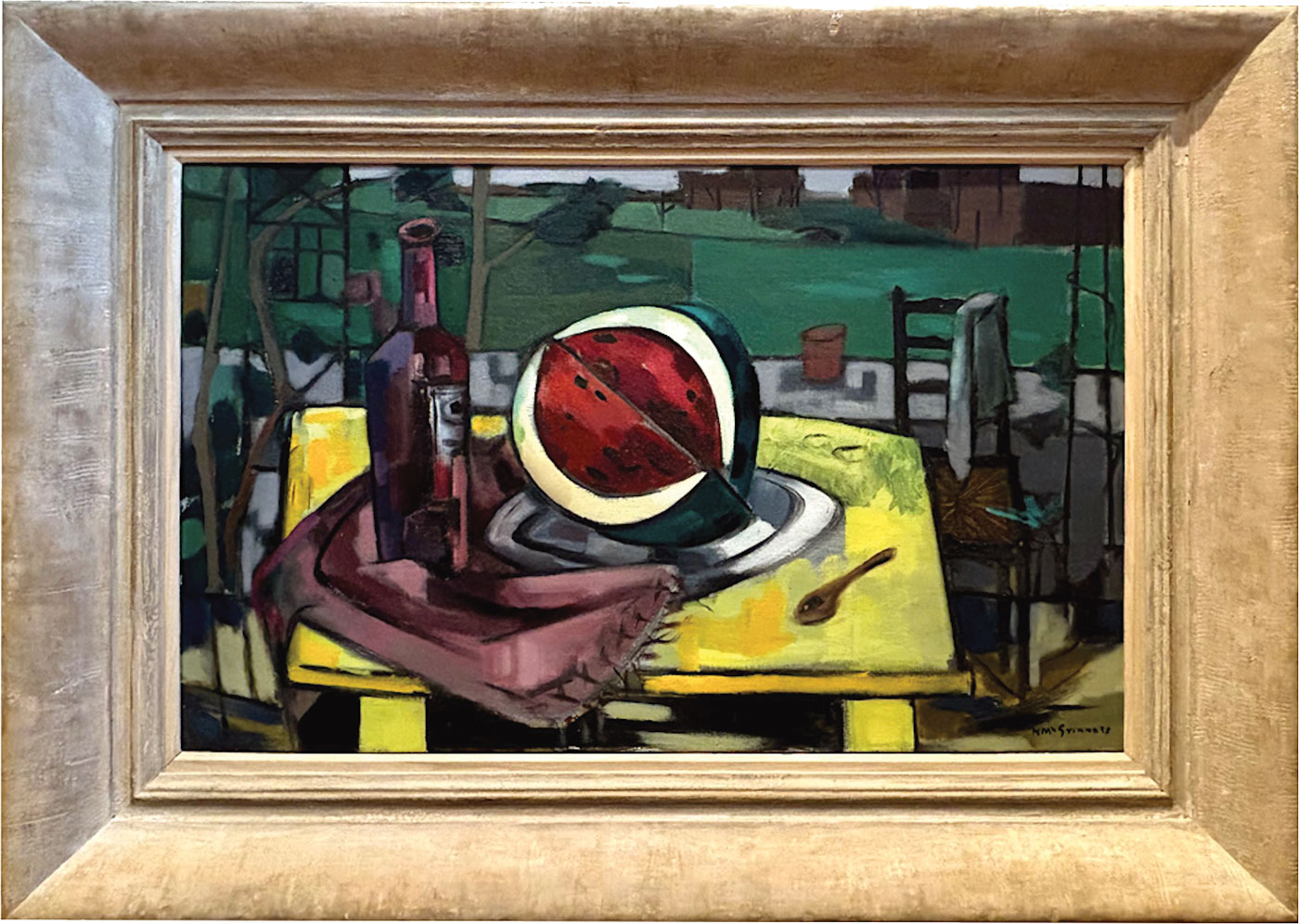

The breadth of Modernist designs available in our inventory during that time led to some wonderful pairings with artist-made and innovative frames. Paintings by Irish Modernists such as Yeats, Gerard Dillon, Norah McGuinness, and Mainie Jellett were aptly reframed by the O’Briens in many noteworthy hand-carved frames of the early to mid-twentieth century. Other works acquired frames designed or carved by artists; a few of our favorites are illustrated in this chapter.

American Arts and Crafts frames represent a return to handcraftsmanship as a rejection of the previous century’s mass-manufactured moldings. Notable American Arts and Crafts framemakers now represented in The O’Brien Collection include Foster Brothers, Boston (est. 1875); Carrig-Rohane, Boston (est. 1903); Walfred Thulin, Boston; Frederick Harer, Bucks County, Pennsylvania; Newcomb-Macklin, Chicago (est. 1883); and New York’s Milch Galleries and Royal Art Company (figs. 15–18). More than a few O’Brien period frames were made by the House of Heydenryk in New York.

fig. 15

Norah Mc Guinness

Melon on Terrace Table | 1950s

21.75 in. x 35 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1930 American Modernist frame, Woodstock, New York artist-made, gray paint over impasto combed gesso on wood.

fig. 16

Mainie Jellett

The Land, Éire | 1940

24.5 in. x 29.5 in., Oil on canvas

Mid-20th century American Modernist frame, rubbed polychrome on hand-carved wormy chestnut wood, patinated gesso on wood liner. Frame provenance: deaccessioned by the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, D.C.

fig. 17

Seán O’Sullivan

The Emigrant’s Return | c. 1962

28 in. x 36 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1937 American Arts and Crafts frame, Walfred Thulin, Boston, maker; patinated white-gold and black paint on hand-carved wood; hand-carved signature verso

19 WT 37 / Thulin / 3046.

fig. 18

William John Leech

The Tea Trolley | early to mid–1960s

30 in. x 25 in., Oil on board

c. 1920s American Arts and Crafts painting frame, Newcomb-Macklin, New York/Chicago makers, gilded hand-carved wood.

Hermann Dudley Murphy was a tonalist painter and founder of Carrig-Rohane, the first American enterprise to offer frames made by artists for artists. He named his atelier “Carrig-Rohane,” a Gaelic reference to the red cliffs of his father’s ancestral Irish home. Every hand-carved and gilded frame made by this shop was painted deep clay-red on the back, incised with Murphy’s M cipher, the signature of the shop, and numbered consecutively. Signing and dating every frame was a testament to each being a work of art. Today, these are among the most valuable American frames. The Carrig-Rohane frame on Jack Yeats’s Sunday, with elegant carved leaf motifs and a stippled gesso panel, is a fine example of that atelier’s superior artistry (fig. 19).

fig. 19

Jack Yeats

Sunday (a.k.a. Sunday Walk) | 1922

9 in. x 14 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1929 American Arts and Crafts painting frame, Carrig-Rohane, Boston makers, gilded-hand-carved wood, hand-carved signature on verso: 19 M 29/Carrig-Rohane Shop Inc./R.C. Vose/Boston #5026.

Buck’s County, Pennsylvania, was also an epicenter of American Arts and Crafts frames in the first half of the twentieth century. The county’s premier frame maker was Frederick Harer. Harer experimented with gilding, wood carving, and incising techniques and filed punches into patterns of his own design, using them to create unique impressions on gilded frame surfaces.

We reframed four Paul Henry paintings, each in artist-designed frames worthy of extra description. Of these, our favorite pairing is In the Kingdom of Kerry, a patchwork landscape of autumnal gold fields delineated by rock walls—shapes that are echoed in the carved beaded borders, incised zigzag patterns, and stepped profile of the signed Harer frame (fig. 20). In Ireland, Paul Henry paintings often turned up in so-called Dutch-style frames, which were satin black with multiple rows of ripple ornament—a style which did not suit the O’Briens’ taste or the higher standard of their collection.

fig. 20

Paul Henry

In the Kingdom of Kerry | 1930–33

19 in. x 21.25 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1910–30 American Arts and Crafts painting frame, Frederick Harer, Bucks County, Pennsylvania maker; gilded and incised hand-carved wood; hand-carved signature on verso: HARER.

Henry’s Reflections Across the Bog is now paired with a deceptively straightforward cassetta design, but in fact, the frame is more complex than it looks. The dark tonality is actually polychrome, with layers of deep pigment hand-rubbed and patinated to create an overall black appearance, revealing subtle undertones of color depending on the light. This finishing technique created a more interesting luminous effect around the painting of light, clouds, and reflections. We replicated the frame from an original frame in our own collection, designed and handmade by the American artist Maxfield Parrish. Like the original Parrish creation, the back is painted viridian green (fig. 21).

fig. 21

Paul Henry

Reflections Across the Bog | 1919–21

24.25. in. x 29.25 in., Oil on canvas

Custom-made replica of c. 1909 American artist-made frame, original Maxfield Parrish design, polychromed wood.

In America, social realist painters like Edward Hopper, John Sloan, and George Bellows specified frames that would not interfere with their depictions of urban modernity. Artists moved away from the coloration and symbolism of traditional gold-leafed frames, instead choosing metal leaf and Roman-gilded finishes—often dark-toned—or muted painted surfaces to create a neutral surround for often gritty, realistic subjects.

Charles Lamb’s The Turf Cutter was reframed in a wide, dark wood profile that acts like a window and relates directly to the painting’s subject, appearing powerful and honest. The wood was plainly carved and retains active tool marks, showing the handiwork of the laborer. In keeping with the modern movement away from traditional gold leaf and ornamented designs, this frame was finished in a process called Roman gilding, a technique of burnishing brass powders and animal glue applied on wood, resulting in a sculptural appearance of solid cast bronze (fig. 22).

fig. 22

Charles Lamb

The Turf Cutter | mid to late 1920s

36 in. x 26 in., Oil on canvas

Early 20th-century American Modernist frame; Roman-gilded hand-carved wood with hand- chiseled patterning.

An elegant dark surround was also selected for Erskine Nicol’s mid-nineteenth-century scene, A Shebeen at Donnybrook (fig. 10). This frame is a rare model by the Boston firm of Foster Brothers, known for their robust adaptations of traditional European designs. Atypical of Foster Brothers, this rich wood frame was not gilded overall. The motifs hark back to early eighteenth-century Italian Canaletto frames with added stylized gilded leaves at the sight edge. Thus, Nicol’s scene appears timeless, crossing centuries in both subject and framing.

When we first visited the O’Briens as frame consultants, a significant painting by Robert Henri stood out to us. The animated portrait of a young Irish lad, Skipper Mick, was inappropriately framed in a dark Louis XIV-revival style—what we call “Park Avenue” mode (fig. 23). Its overwrought ornamentation suited neither the simple subject of an Irish youngster nor the modernity of the artist. Sometimes dealers and collectors chose “fancy” frames like this to “upsell” or make artwork look more important, but on this painting in particular, with its spontaneity and active brushwork, the formal frame style was out of sync. We proposed several other frame designs but none were decided on at that time. Then several years later, a kind of frame miracle occurred. Sorting through a random collection of old frames, we stumbled on a simple gilded frame, somewhat worn, which at first glance didn’t seem to warrant any special scrutiny. But it is always recommended to examine the back of a frame before passing judgment, and this one happened to have bold, black, hand-painted lettering along one side: “ROBERT HENRI / 10 GRAMERCY PARK / NEW YORK. N.Y.” The adjacent molding bore the hand-carved signature “LAURENT.” We realized that this frame had belonged to Robert Henri, and the frame had been made by Modernist sculptor Robert Laurent, who was known for his direct relief carving. Laurent also made frames as a means of making a living and in collaboration with important artists including Robert Henri and Childe Hassam. Like Henri, Laurent taught at the Art Students League in New York City. I remarked that we were still searching for the right frame to propose for Skipper Mick, and we should check if this frame was close in size. Unbelievably, as we pulled the frame out of the box, we saw a hand-lettered, gilded nameplate, “Skipper Mick ROBERT HENRI,” affixed to the front (fig. 24). We checked the frame size; it would exactly fit the O’Brien painting!

fig. 23

Robert Henri

Skipper Mick | 1924

23.4 in. x 19.5 in., Oil on canvas

Before reframing:

20th-century Louis XIV-revival style frame, gilded applied

ornament on wood.

fig. 24

After reframing:

c. 1924 American Arts and Crafts artist-made frame; Robert Laurent, New York maker; custom frame commissioned for this painting by Robert Henri; gilded hand-carved wood; hand-carved signature on verso LAURENT/CK [or CR]; hand-painted signature on verso ROBERT HENRI/10 GRAMERCY PARK/NEW YORK. N.Y. This original period frame was donated to the O’Brien Collection by Gill & Lagodich.

It is rare in our profession to make a discovery of the original frame for a painting by a significant artist carved by another important artist. It delighted us to have had this stroke of luck and to reunite the original frame with the original painting. This frame is an important addition to The O’Brien Collection, and we were proud to be able to donate it as part of the historical and aesthetic record of Skipper Mick’s journey. These rare lightning strikes remind us why we are in the business we are in and why we continue to be entranced by ongoing frame scholarship. As a bit of icing on the cake, we very recently discovered a similar Laurent frame on an earlier Henri portrait in another private collection, which reinforced that this was a frame design liked by both artists.

We subsequently placed a different Robert Laurent frame model in The O’Brien Collection, for Yeats’s A Man Sure of His Welcome (perhaps the best painting title, ever) (fig. 25). Though not made for this specific artwork, the mellow gilding and wide beveled profile that shows undulations from the artist’s chisel appears like a sunlit window into the barroom scene, with its genial subject filling the frame. Though very different in painting style, both artists, Henri and Yeats, were notable Modernists. Pairing an artist-made frame of the period with their work further complements the spirit and generation of both painters and the frame maker. We think all three artists would be pleased with the choice.

fig. 25

Jack B. Yeats

A Man Sure of His Welcome | 1945

9 in. x 14 in., Oil on board

c. 1920s American Arts and Crafts artist-made frame; gilded hand-carved wood; Robert Laurent, New York maker; carved signature on verso LAURENT.

As noted, the transition from traditional gold to humbler materials for frames parallels the progression of subject matter from academic realism and Impressionism of the late nineteenth century to social realism, with its scenes of everyday man, represented in America by the so-called Ashcan School. The frames chosen by American artists of this period lend themselves naturally to the more rural and urban Irish subjects, depictions of everyday life, not necessarily precious portrayals or formal portraits.

A very fine example is the Carl Sandelin frame on Gerard Dillon’s Mending the Nets, Aran (fig. 26). Sandelin was a New York frame maker whose handmade frames can be seen on many works by American painter Edward Hopper. We don’t know the painting for which this frame was commissioned, but as testament to the artisan’s pride in his work, he inscribed in the gesso on the back “frame made for Midtown Galleries by Carl Sandelin framemaker.”

fig. 26

Gerard Dillon

Mending Nets, Aran | late 1940s, early 1950s

33.21 in. x 35.25 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1930s–40s American Modernist frame, Carl Sandelin, New York, maker; rubbed polychrome on combed and incised gesso on hand-carved wood; signature hand-written in gesso on verso: Frame made for/Midtown Galleries by/Carl Sandelin Framemaker. Torn paper label verso: MIDTOWN GALLERI…/A.D.GRUSKIN DIR…/11 EAST 57TH STREET NEW../PP..G PLANTING.

What’s fascinating about many Modernist frames is that they are often traditional frame moldings modified without ornament or gilding, instead textured or incised or made of wormy wood and finished in toned gesso, rubbed leaf, and painted or clay-like finishes to create surface interest.

The Modernist combed gesso frame on William Conor’s Homewards has a surface as complex as the canvas (fig. 27). From afar it looks merely textured white, but up close one can see flecks of blue and red beneath the scumbled gesso finish. Also of note is how the frame profile slopes gently backward toward the wall, presenting the painting further forward in the frame, closer to the viewer.

fig. 27

William Conor

Homewards | date unknown

18 in. x 14 in., Crayon on card stock

c. 1940s–50s American Modernist frame, stippled polychrome and scumbled gesso on wood.

A favorite pairing is Gabriel Hayes’s Cork Bowler with a hand-carved Modernist frame, whose faux marble painted finish complements the rock wall and scattered stones in the foreground. The robust carving supports the attitude of the bowler, caught midstride, arm poised to throw his iron ball. This one-of-a-kind frame, scarce in such a large size, had been deaccessioned years ago by the Hirshhorn Museum, and we had the good fortune to acquire it, holding it back to offer for just the right painting (fig. 28).

fig. 28

Gabriel Hayes

Cork Bowler | 1941

49 in. x 37 in., Oil on board

c. 1940s–50s American Modernist painting frame, white and gray polychrome dappled painted finish on hand-carved wormy chestnut wood. Frame provenance: deaccessioned by Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, D.C.

Interestingly, the carved wood frame styles that most suited a majority of paintings in The O’Brien Collection were made by the House of Heydenryk, New York. From 1939 through the 1950s, Henry Heydenryk produced a series of frames hand-carved of wormy chestnut wood and colloquially referred to as “driftwood.” Purportedly inspired by the availability of unusual wood resulting from a chestnut tree blight in the 1920s and 1930s, these frames were not gilded and were finished instead with a pickled or painted patina that enhanced the unusual texture of the wood. Wormy chestnut frames are a popular choice for framing American Modernist works of art.

Seán Keating’s King O’Toole is a powerful portrait that is well supported by the strong carving and organic appearance of its frame. The pale wash of paint over the wormy wood surface emphasizes the rusticity of the subject. This Heydenryk frame design was developed for the American Modernist painter and poet Marsden Hartley and loaned to that artist for his first exhibition in 1938 (fig. 29).

fig. 29

Seán Keating

King O’Toole | 1930

26 in. x 30 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1930s–40s American frame; House of Heydenryk, New York, makers; polychrome wash on hand-carved

wormy chestnut wood.

Other Modernist frames, many by Heydenryk, enhanced with washes of color or varicolored pigments rubbed into rough wood to enhance the texture and carved patterns, were chosen for paintings in The O’Brien Collection by William Conor, Lilian Davidson, Gerard Dillon, Colin Gill, William Leech, Louis Le Brocquy, John Luke, Harry Kernoff, Norah McGuinness, Walter Osborne, Aloysius O’Kelly, and Jack Yeats (figs. 30–35).

fig. 30

William Conor

The Launch | 1923

30.25 in. x 25.25 in., Oil on board

Custom-made replica of c.1940s American frame, House of Heydenryk, New York, maker; polychromed hand-carved distressed wormy chestnut wood, black-painted frieze.

fig. 31

Gerard Dillon

Fighting Tinkers | 1950

16 in. x 20 in., Oil on board

c. 1940s French Modernist frame, polychromed hand-carved wood.

fig. 32

William Conor

The Donkey Cart | 1923

24 in. x 20 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1940s American frame, House of Heydenryk, New York, makers; polychromed wormy chestnut wood.

fig. 33

William Conor

The Jaunting Car | 1930

24 in. x 20 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1930s–40s American frame; House of Heydenryk, New York, makers; polychrome wash on hand-carved wormy chestnut wood, patinated gesso on wood liner.

fig. 34

William Conor

The Street Dance (a.k.a. Eleventh Night) | c. 1920s

24 in. x 22 in., Colored chalk on paper

Custom-made replica of c. 1940s–50s American frame, House of Heydenryk, New York makers, rubbed gilded and polychrome finish on hand-carved wormy chestnut wood.

fig. 35

William John Leech

The Housekeeper | late 1950s

32 in. x 24 in., Oil on canvas

c. 1940s American frame, House of Heydenryk, New York, makers, hand-carved wormy chestnut wood with green painted frieze.

A frame is the home, context, and stage for the painting, and so much of Irish art is live performance, whether spoken word or song, or a moment or activity captured by the painter’s brush. More than any other collection we have worked with, the in-depth concentration on cultural cohesiveness was paramount. It was clear to us that the ongoing formation of The O’Brien Collection was reaching deep into Irish identity and culture. In proposing complementary and often unique frames for the Collection, we strove to help preserve different facets of the rich traditions depicted in each work.

My partner Simeon Lagodich and I were honored to be invited to participate in and contribute to this important legacy project by providing new windows onto familiar scenes, framing the Irish traditions to bring them forward into our current history, and helping to create new artistic settings for The O’Brien Collection of significant Irish artists.

“A frame is the home, context, and stage for the painting, and so much of Irish art is live performance, whether spoken word or song, or a moment or activity captured by the painter’s brush. More than any other collection we have worked with, the in-depth concentration on cultural cohesiveness was paramount. It was clear to us that the ongoing formation of the O’Brien Collection was reaching deep into Irish identity and culture. In proposing complementary and often unique frames for the Collection, we strove to help preserve different facets of the rich traditions depicted in each work.”

—TRACY GILL